Background to the research

Between 8 and 36 weeks of pregnancy, the brain of a growing baby (the fetus) includes an area called the germinal matrix. It produces cells that are important for signalling. These signals control different processes in your body, such as movement, eyesight and pain sensation. Once the baby’s brain has developed, these cells make up what is known as the grey matter of the brain.

The germinal matrix is very fragile. It’s filled with blood vessels which sometimes burst when a baby is born preterm. This kind of bleeding is called germinal matrix hemorrhage and can lead to serious complications with how the brain works during a person’s life. It may even cause death.

Why is this type of research important?

It’s difficult to prevent germinal matrix hemorrhage in preterm babies. When it does occur, we currently have some treatments which try to reduce its negative effects on the child. We need to find more effective ways to treat it, and these need to be tested thoroughly by scientists in the lab before they can be used by humans.

What were the aims of the research?

The aim of this study was to develop an animal model which can be used by other researchers to help better understand germinal matrix haemorrhage and allow them to test new ways to either prevent or treat this type of brain injury in humans.

The researchers wanted to adapt and improve upon an existing model. To do so they used rats whose stage of brain development was about the same as that of a human fetus, or a baby born early, at 26–32 weeks of gestation.

This was an improvement to the current model in which the rats were older and whose brain was more developed – similar to the development stage of a human baby born at term – and when the germinal matrix was less obvious or non-existent.

How was the research done?

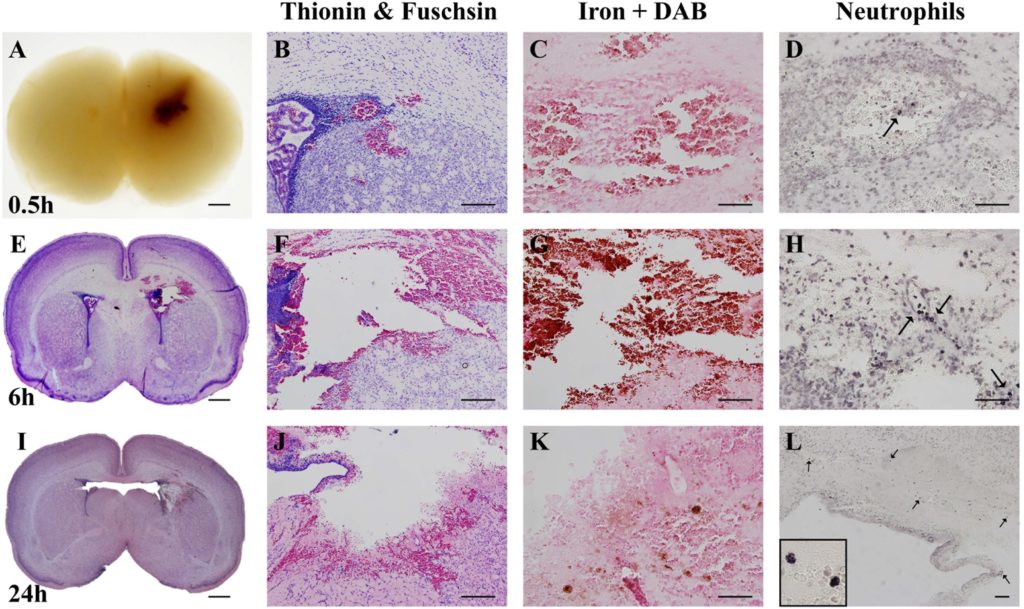

This study looked at what happens when severe bleeding takes place in the brain’s germinal matrix. To do this, the scientists carried out experiments using rats whose stage of brain development was about the same as that of a human fetus, or a baby born early, at 26–32 weeks of gestation.

The study involved different groups of young rats. One group was injected with an enzyme called collagenase to speed up the rupturing of the blood vessels and bleeding in the germinal matrix.

The control group was injected with a saline (salt) solution. Saline is given because it’s expected to have no effect on the animal, allowing the scientists to compare the rats with and without brain injury.

The rats were given an anaesthetic before being injected with collagenase or saline and were allowed to recover afterwards. The group which was injected with collagenase experienced bleeding in the brain – germinal matrix hemorrhage – almost immediately.

Over several days, the scientists ran tests to compare the groups. This included checking the weight, coordination, reflexes and anxiety levels of all of the rats to see how the ones with germinal matrix hemorrhage compared to the animals without brain injury.

What did the research show?

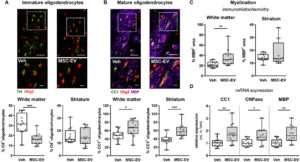

The researchers found that the animals with germinal matrix hemorrhage performed worse in behaviour and movement tests. They also opened their eyes later than the rats which did not have bleeding in the brain. The injured rats also showed different levels of red blood cells and iron to the other groups, as well as a loss of brain tissue.